I’m really excited to be part of a sequence of blogs – a symposium – on writing in science coordinated by Pritesh Raichura.

- Pritesh started the sequence last week in his post (here).

- Ruth’s post ‘Sentences and the Web of Knowledge’ (here).

- Targinder’s post ‘Writing Revolution Activities in Primary Science’ (here).

- Jasper’s post ‘Writing in Science – exposing and extending’ (here).

My post is on the atoms of scientific literacy: words. Beck, McKeown and Kucan in the definitive vocabulary book: Bringing Words to Life (2002) categorise vocabulary into tier one, tier two and tier three words.

We use tier one words all the time: they don’t need explaining. Words like: house, cat, climb are tier one.

Tier two words are sophisticated words, not necessarily used at home, but often used in more academic contexts – in a debate, a newspaper article, or a science textbook. Words like exacerbate, context, exotic. These words are not subject specific and they are every teacher’s responsibility to teach.

This post is about tier three words. These are the subject specific words which either belong solely to a subject (e.g. fission, chloroplast, ionic bond), or also have a less disciplined life in the outside world (e.g. charge, respire, work).

Many tier three words look like two or more words, but behave like a single word (e.g. ionic bond, inclined plane and chemical store of energy).

In this post I describe some characteristics of tier three science words and recommend three tools for teaching them.

Characteristic #1: A definition of a tier three word is only useful after you have learnt what the word means.

Here is a definition:

Chemical energy is energy stored in substances. This energy is released by your body when you digest food, and by cars when fuel is burnt. Wood, paper, apples, petrol and batteries all contain chemical energy.

http://www.futuresparks.org.au/media/2302/pearson_science_8_sb_chapter_5_unit_5.1.pdf

Imagine you were a year 7 pupil – would you be able to use this definition to decide whether a glass of water is a chemical energy store? A definition isn’t the best place to begin. Instead start with lots of examples (and non-examples).

Characteristic #2: Tier three words are not really concrete, even if they seem to be.

You are teaching year 7 pupils lab equipment. You hold up a beaker. You say, “This is a beaker.” You quiz them. They tell you it’s a beaker. Beaker is a tier 3 word because it is a technical term.

It is possible to have a very shallow, concrete understanding of many tier three words: words like beaker, Bunsen burner, push and pull.

But these words can’t stay concrete if they are to be useful. When a professional chemist uses a beaker, she has a much richer, abstract understanding.

Your job, as a science teacher, is to help learners develop the rich abstract layers of understanding associated with even the most concrete piece of laboratory equipment.

Characteristic #3: Tier three words gain meaning from context.

We learn tier three words in relation to other tier three words. If the surrounding network of words is insecure, the learner will struggle to make sense and retain the meaning of the new word.

Characteristic #4: We typically choose tier three words independently of texts.

Many of the blog and books about vocabulary focus on tier two words. Teachers identify which tier two words to teach based on the text they are reading.

Tier three words are usually chosen independently of texts – their choice is often not down to the teacher, but planned at the time of writing the course. For example, any electricity course is likely to include the tier three words: current, potential difference, cell and conductor.

Tier three words are different to tier two words. They require different teaching strategies and tools. Below I describe three tools I find useful in my science teaching.

Tool #1: Provide multiple examples (and non-examples)

This strategy comes from Engelmann’s Direct Instruction.

A fast way of developing the schema surrounding a tier three word is to show plenty of examples and non-examples.

Learners are shown dozens of examples of the concept, but they are also shown non-examples – similar situations, but which are not examples.

The teacher is clear about whether the image is an example of not. After the first round of examples/non-examples, learners are quizzed with increasingly tricky examples and non-examples.

When learners already have a developed understanding of what a word means, a definition can become useful. I like to use a Frayer Model which includes a definition as a follow on activity (sometimes weeks later).

Tool #2: Make the schema explicit

It is important to build the new word into a framework of existing knowledge. Otherwise the knowledge becomes a needle in a messy haystack (see here and here). Show how the word is related to other concepts to help learners organise their schemas (show them how your schema words – don’t just ask for theirs).

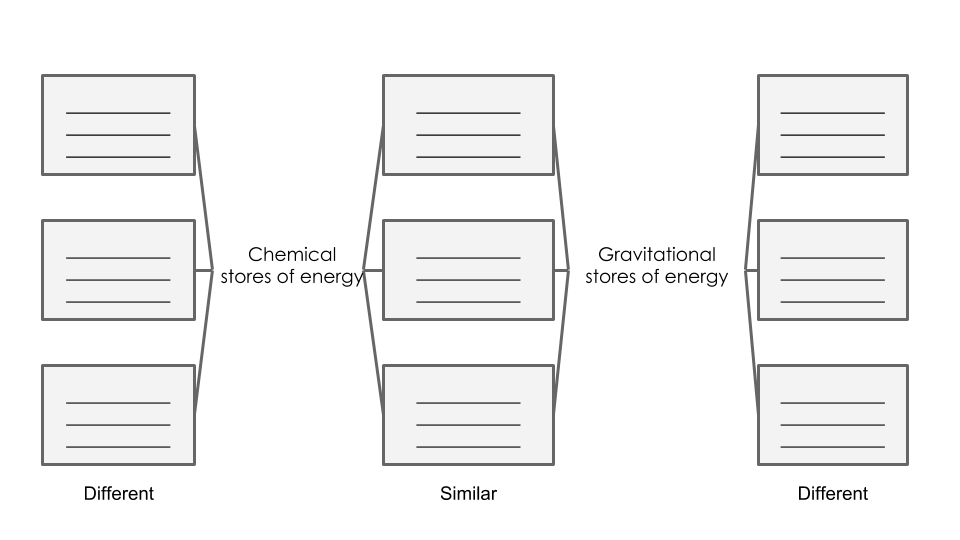

Mind-maps are great, but I love a similar/different task too:

Similar/Different

An effective strategy for connecting new knowledge into existing schemata which uses both retrieval practice is Similar/Different. Learners think about the differences and similarities between the new concept, and a previously learnt, similar concept.

A possible outcome:

Tool #3: Practise, practise, practise

Over-learning is a good thing (see here) so practise, practise, practise. Practise retrieving the word from memory in quizzes (one word answers), labelling diagrams (e.g the parts of a cell), multiple-choice questions and gap-fills (but be careful with gap-fills. Often learners can work out the missing word, without having to retrieve the word from memory).

Using the word in sentences is an excellent strategy, but that’s for the next blog in the sequence, by Ruth Walker….

Thank you for reading!

Ben

@BenRogersEdu

Further Reading

- Beck, McKeown and Kucan: Bringing Words to Life (2002)

- Beck, McKeown and Kucan: Creating Robust Vocabulary (2008)

- Didau: The Secret of Literacy: Making the Implicit Explicit (2014)

- Quigley: Closing the Vocabulary Gap (2018)

- Lemov: Reading Reconsidered (2016)

- Hochman and Wexler: The Writing Revolution (2016)

- Willingham: The Reading Mind (2017)

Is water not a chemical store of energy …

LikeLike

Great post as ever Ben. I don’t follow this bit though: “We learn tier three words in relation to other tier three words. If the surrounding network of words is secure, the learner will struggle to make sense and retain the meaning of the new word.” – do you mean insecure?

LikeLike

Thanks Adam – that got past 3 proof reads! Will correct. Ben

LikeLike