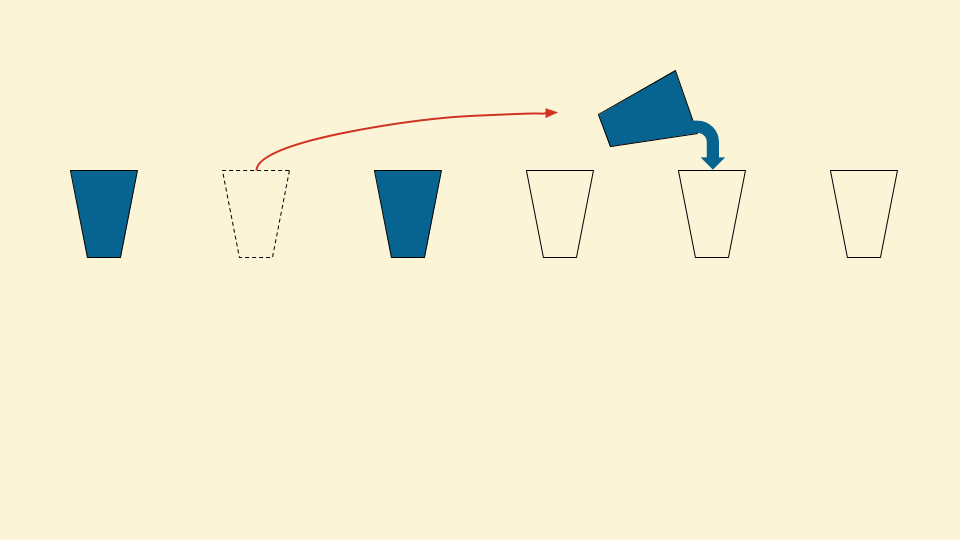

In class, I’m mostly watching hands. There’s a problem I like to set which gets people’s hands waving like windmills. It’s called the six-cup problem.

The problem: you have six cups in a row. The left hand three are filled with water and the right hand three are empty. You are allowed to move one cup only. How can you make it so that the row of cups is: full, empty, full, empty, full, empty?

Try it now (answer at the end!)

I’m hoping that when you tried to solve it, you couldn’t keep your hands still – most people use one of three strategies:

- get a pen and paper;

- act out the problem using hands and fingers or

- get six cups and a jug of water.

It is a well researched problem with high cognitive load (you have to remember the position and state of the three cups). Barbara Tversky’s beautiful 8th Law of Cognition states:

“When thought overflows the mind, the mind puts it back into the world.”

It’s really hard to solve this problem with your hands still.

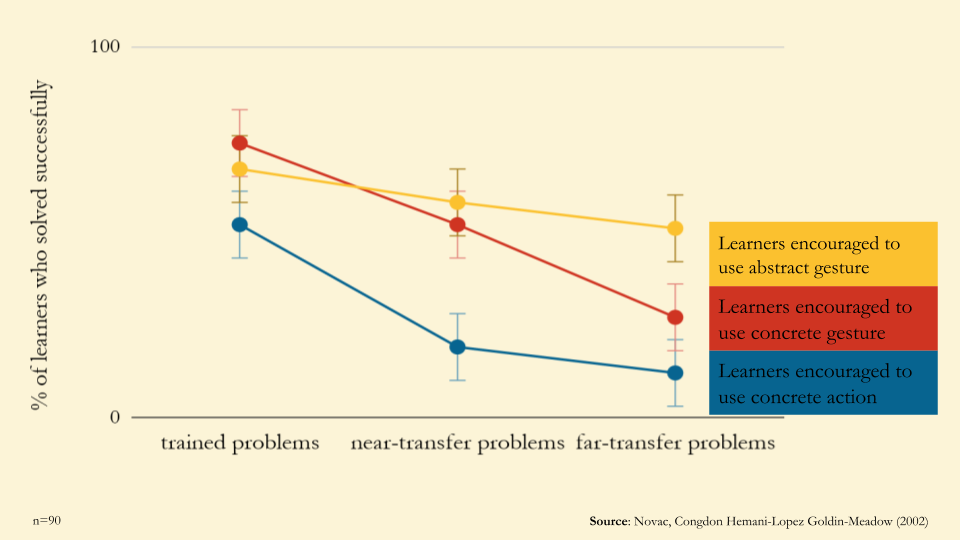

There are implications for the classroom: training you learners to use abstract hand gestures leads to better novel problem solving. It did in this paper anyway: Novac, Congdon Hemani-Lopez Goldin-Meadow’s 2002 paper: “From Action to Abstraction Using the Hands to Learn Math”

90 pupils, who had been unable to solve problems like this:

2 + 9 + 4 = ⬜ + 4

were split into three training groups. Group one were trained to solve it by physically moving magnetic numbers. Group two used concrete hand-gestures representing the movement of the digits. The third group were trained to use an abstract gesture to help solve the problem. The results were surprising (to me):

- Physically manipulating the numbers was useful when the problems were almost identical to solve, but their usefulness dropped as soon as the problems changed.

- Gesturing the movement of the digits was more helpful than physically moving the numbers (weird no?).

- The most effective action for near and far transfer was to use abstract gesture.

Conclusion

So, it’s a stretch to say that this applies more generally, but there is plenty of evidence to show that gesture helps with thinking – and it’s cheap. I’m pretty sure you use gestures when you teach, but encourage your learners to use them too – it can’t hurt, and could make a difference.

Ben

Solution to the six-cup problem:

There’s definitely good research to back that the notion that learning certain kinds of abstract ideas is better supported with abstract representations than it is with concrete representations. This one I think is a good example. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/320/5875/454.full On the other hand, students can become fluent at working with abstract representations and not develop skills to connect them to concrete contexts. Both are important and I don’t think there is a single ideal path of concreteness to abstractness that is independent of the knowledge / skills you are expecting to be learned, and even what aspects of that knowledge / skill you are emphasizing— alignment, fluency, span, etc.

LikeLike

Thanks Brian, thanks for the link. Primary maths colleagues I’ve learnt from are always moving up and down the ladder of abstraction – it strikes me as vital to keep concepts anchored in reality as you say.

LikeLike