(How IA interprets this text)

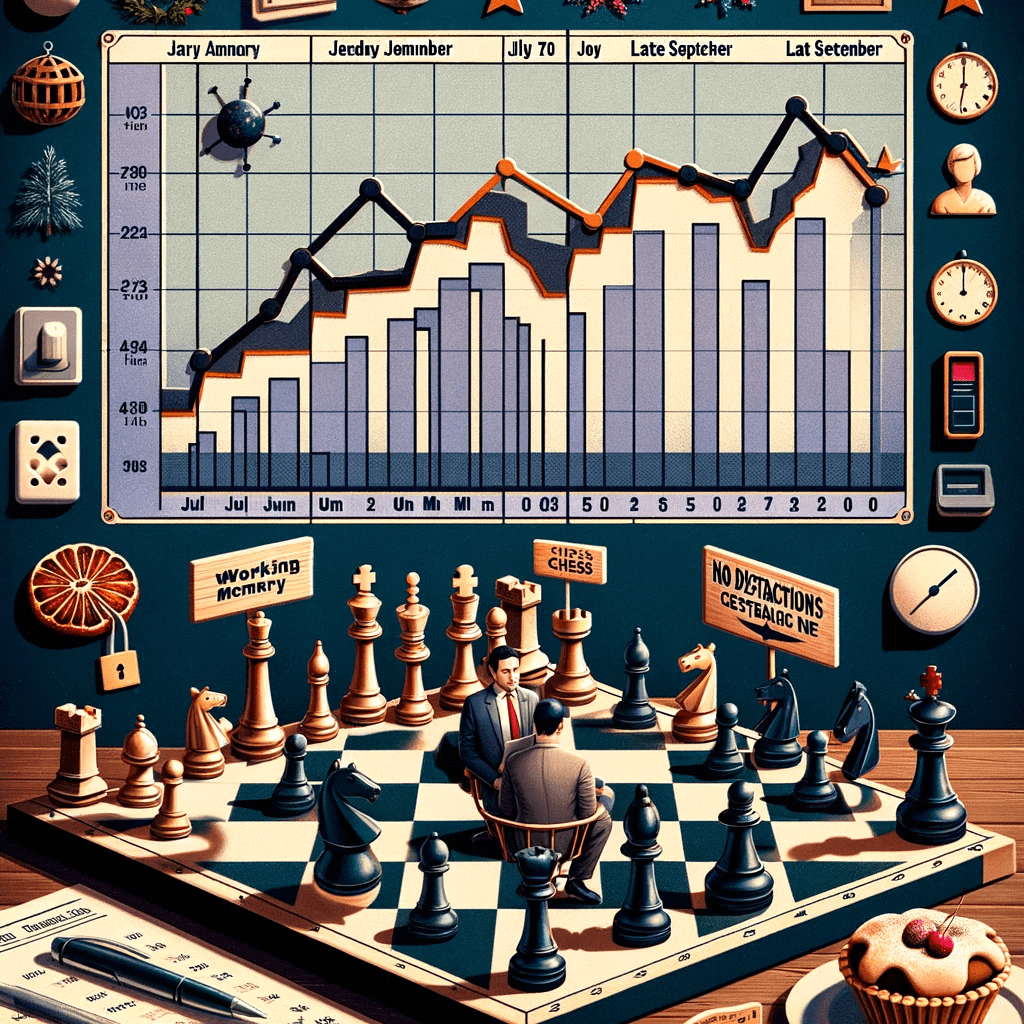

I have played 226 games of rapid (10min) chess this year, and I’ve ended up with the same rating I started with.

So, after 70+ hours of play, I’ve not improved. This isn’t surprising: I’ve not taken lessons, done drills or reflected on any of my games. I just enjoy playing.

My end of year stats are in and I am curuios.

My chess rating steadily decreased between January and June; then between July and late September it rapidly increased, only to sharply decrease again from October.

Are you seeing what I’m seeing?

Let’s assume my chess ability hasn’t changed. The chess content of my long-term memory is likely largely the same, so it must be my executive function that changes throughout the year. There are three main executive functions: working memory; inhibitory control and switching. Let’s pick this apart.

Working Memory

Working memory has been big news in education for a decade: it’s where we solve problems. It’s plausible that my working memory capacity decreases as the term progresses, but I think other factors also have a role.

Inhibitory Control

Early years teachers are more aware of this executive function than teachers of older children, but it’s really important for all learners. Inhibitory control is about ignoring distractions: the distractions going on around us, but also within us. Our inhibitory control filters out the irrelevant retrieval of memories bombarding our working memories.

For my chess, I tend to play where it’s quiet (no music, no podcasts, no chat), so that’s not the issue. But my annual dip in performance could be related to reduced inhibitory control as I get distracted by my own thoughts.

Cognitive Flexibility – Switching

The third executive function lets me switch from one task to another. In a rapid chess game, I can usually focus on the whole game (unlike daily chess where I have to return to the game after several hours of other tasks). But switching also includes trying several moves in my head, and then comparing. While tired, I often rule out one move, then try another and forget that the first move was disastrous… which I then choose.

Conclusions?

I’m sure this says something useful about learning and performance, but mince pie.

Happy Christmas 🙂

Ben