For years I have struggled with teaching “Working Scientifically” in science lessons. It is a core strand from Key Stage 1 to Key Stage 3. In fact, it is the most consistent strand between primary and secondary. But it doesn’t make sense. I have three main objections.

Objection #1

My first objection is that working scientists don’t think about “Working Scientifically” : they have internalised acceptable and effective processes through a huge number of examples. It works through a scientific apprenticeship rather than a philosophical model.

“most scientists tend to understand little more about science than fish about hydrodynamics.”

Imre Lakatos (philosopher of science).

Teaching ‘How Science Works’ isn’t a pathway to becoming a scientist. It belongs to philosophy of science and is highly disputed. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t teach it, but we need to be clear about why we are teaching it.

Objection #2

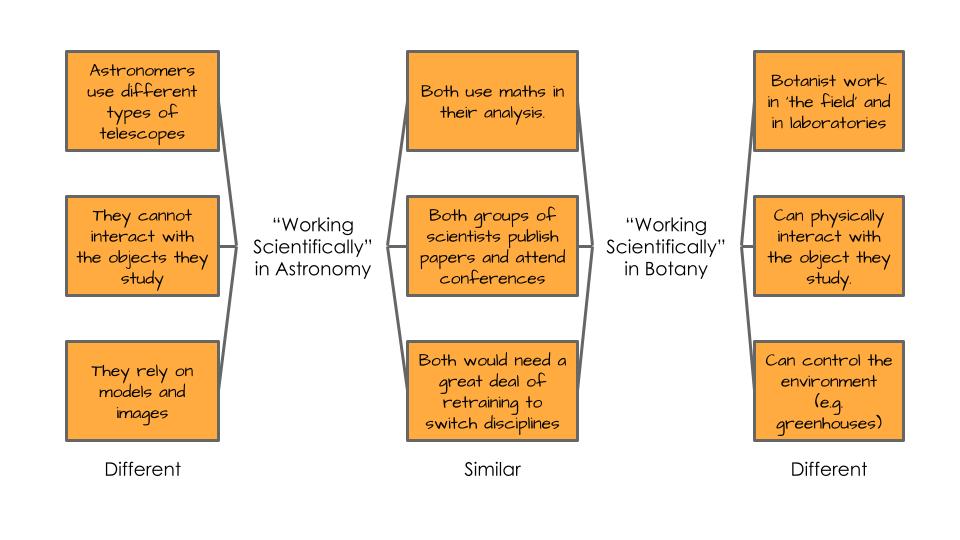

“Working Scientifically” isn’t one thing: it is different for each branch and sub-branch of science. For example, “working scientifically” for an astronomer bears little resemblance to how a botanist works.

It makes sense to teach children “how we know this” within topics. For example how do we know plants need light? How do we know that the planets orbit the Sun? It doesn’t make sense to create an abstract philosophical system to bring these very different methods together.

Objection #3

The National Curriculum abstracts “Working Scientifically” into types of enquiry which can be applied to each topic. I am most bewildered by ‘classification’ as a type of scientific enquiry. It is unreasonable to believe that children are capable of categorising astronomical or botanical objects in a meaningful way. (It is unreasonable to believe that an astronomer could categorise plants or a botanist astronomical objects). Learning ‘how to classify scientifically’ makes no sense. All of the “types of enquiry” specified in the National Curriculum are problematic in this way.

These types of scientific enquiry should include: observing over time; pattern seeking; identifying, classifying and grouping; comparative and fair testing (controlled investigations); and researching using secondary sources.

Science programmes of study: key stages 1 and 2: National curriculum in England

How Could We Teach “How Science Works” in a Meaningful Way?

It is valid to teach children how our scientific knowledge is created. This should be example-by-example, not by teaching a (deeply flawed) philosophical model of how science works.

For example, we might teach how Galileo gathered evidence for the heliocentric model using a telescope or how botanists classify trees into deciduous and evergreen. The Galileo example would be best taught as history of science. It would be great if pupils could observe the moons of Jupiter; the phases of Venus or the mountains on the Moon through a telescope (this is tricky to organise even if you are confident), but understanding the implications of these observations requires explicit teaching. The botany example might best be taught through a ‘field study’ nature walk combined with explicit teaching.

The key is that there is no need for the teacher or the pupils to think about abstracted ‘enquiry types’ – these are a distraction. Instead, let them build up a schema of examples and models of how different scientists have developed new scientific knowledge. I think this will be as much through historical storytelling as through practical enquiry activities – though a combination might be most effective. The key though (and the hardest part) is helping children follow the argument: why does observation x convince us that y is true?

I’ll end with one of my favourite quotes on how science works by philosopher Robert Crease:

“scientists working in a laboratory should be compared to a jury who place themselves for a short time in isolation to evaluate evidence. The jury members bring their experience to being able to judge fairly. Those who think that hard-and-fast rules can be drawn up to guarantee justice have never been on a jury.”

Robert P Crease

Further Reading

I’ve enjoyed these papers:

- Tracking the Footprints Puzzle: The Problematic Persistence of Science-as-Process in Teaching the Nature and Culture of Science – Ault and Dodick

- Epistemology for the Masses: The Origins of “The Scientific Method” in American Schools

– John L. Rudolph

Ben