This is an amazing piece of research. The researchers were able to show that children as young as four are able to understand the science in a text that is read to them; use it to overturn a very common scientific misconception and to apply this understanding to a new context. It shows that even very young children can understand abstract scientific ideas and apply them to new contexts.

In this blog, I have summarised the research and conclude with a question to academic educators – why aren’t we doing more of this sort of research?

original paper: “Do objects of different weight fall at the same time? Updating naive beliefs about free-falling objects from fictional and informational books in young children” – Vaunam P. Venkadasalam and Patricia A. Ganea

Why this is an interesting paper

I’ve been interested in stories and teaching for years. My book is full of stories about physics discoveries. Physics stories drew me and Richard Brock of King’s College together. With Liam Cini O’Dwyer, we’ve carried out our own research on stories in Physics.

This paper is about using scientifically informative texts in early years teaching – can young children (4-5 year olds) learn tricky scientific ideas by being read books? The authors use three different books to compare the impact. One is a control book about a different scientific concept. One is a scientifically accurate fiction about the concept, and one is a straight explanatory text. The texts are all linguistically equivalent.

The authors use a pre and post test to check for understanding. A fascinating thing about these tests is that they support the child to apply their new learning from one context to another. This is really difficult, yet many of the children were able to do this. Many older students would struggle.

Intervention

Two versions of the text were read to the children: an explanation text and a fictionalised account explaining the same scientific concept.

Image from the texts

| Luke and Alice climbed to the top of the jungle gym. “I wonder what happens if you drop two things at the exact same time?” Alice asked. Luke said “Our buckets are the same size. But my bucket is full of toys and your bucket’s empty. I think my bucket’s going to reach the ground first. “No way!” Alice exclaimed. | What happens if you drop two things at the exact same time? Let’s find out how two different objects fall when they are dropped together. First, look at these buckets. These two buckets are the same size. But one bucket is full of toys and the other bucket is empty. |

Extracts from the two texts side by side for comparison.

The stories were read to the children twice after the pre test. The reader asked each child the same questions while reading.

Pre/Post-test

The pre and post test is really interesting. The authors use small weights (beads) to assess the children’s understanding. The weights come in pairs – some weigh the same and look the same. Some weigh the same but look different. Some look the same but have different weights. Some look different and have a different weight.

Children are asked to predict which weight will land first.

| Same shape – same weight They should land at the same time. | |

| Different shape – same weight They should land at the same time. | |

| Same shape – different weight They should land at the same time. | |

| Different shape – different weight They should land at the same time. |

The authors used weighted beads to test whether children could apply their understanding of the concept in a new context

Results

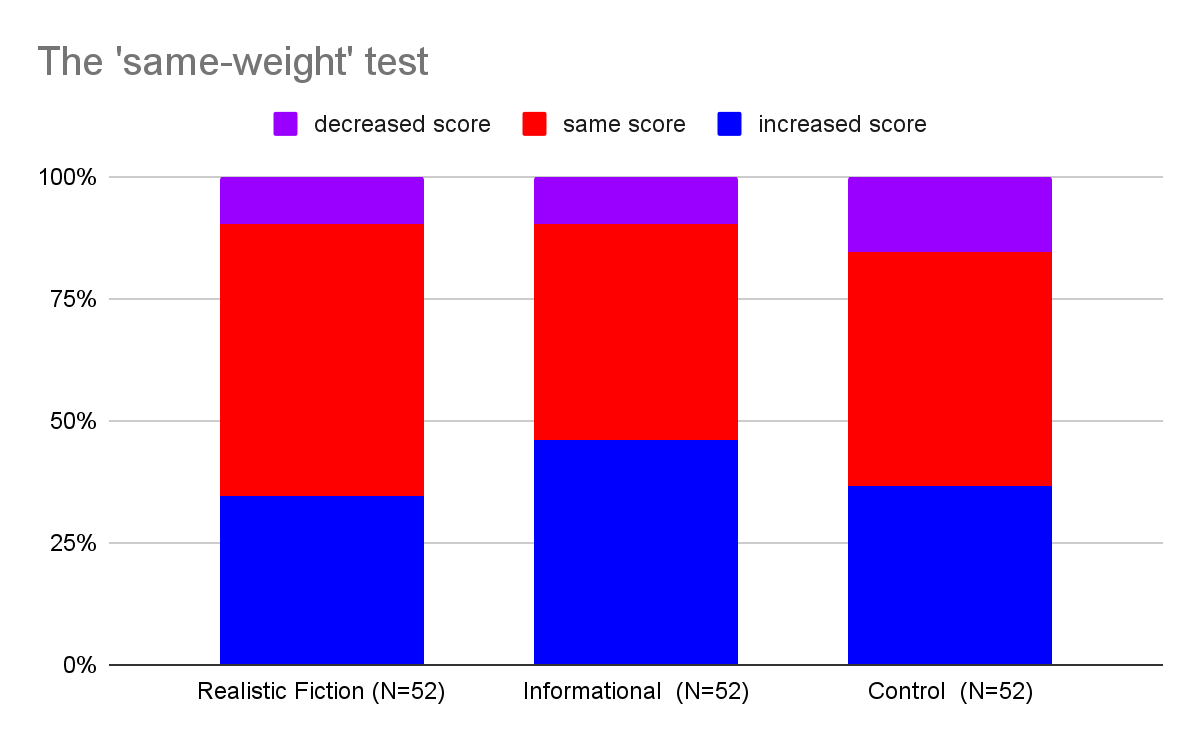

In the same-weight test, objects with the same weight were used to ask children which would land first. The correct response is that both would land at the same time. This is a fairly obvious conclusion once your attention is drawn to the weight of the objects and it isn’t very surprising that the choice of text makes little meaningful difference.

However, in the different-weight test, the texts make a big difference. The correct answer, that both objects will land at the same time, is counter intuitive. You can see that for the control group, reading an unrelated text made very little difference to the outcome. But both the informational and the realistic fiction tests, around half of the children improved their scores.

Just to remind you – these children were able to:

- Comprehend the meaning of the text;

- Overcome a very common misconception which affects a large number of older children and adults and

- Apply this understanding to a new context (from buckets to beads).

This is amazing. Educators should be buzzing like flies trying to replicate this, to see whether the effect can be replicated; whether it works with different groups of children; how long the effect lasts and whether it works for other scientific concepts.

So why aren’t we?

Why Don’t We Do More Research Like This?

It should be easy to study learning in schools. The children are predictably in one place; we have access to information about their family’s economic status, their special needs; their sex; their age; their prior attainment. The data is rich. We could track the learning impact for years. It would be straightforward to train TAs to deliver the pre and post tests and the interventions. We could amass data very quickly and efficiently.

But no academic institution, funding body or journal would touch it. Young children can’t give consent for an experiment to be carried out on them, and getting parental consent is really difficult. When Richard Brock, Liam Cini O’Dwyer and I carried out our research on stories, we used sixth formers, because getting their informed consent is so much easier.

Carrying out research on non-consenting children is ethically challenging. The guidance on this was developed after the holocaust, which makes it very difficult to argue against. On the other hand, when the research involves choosing one text over another and testing whether children learn more effectively, it is also unethical not to carry out the research.

So I would like to see schools and academy trusts working ethically and safely to carry out their own internal research like this and publishing the results in blogs and on their websites. We could learn so much about learning, so quickly. We could be so much better informed about teaching science to our children.

Please comment, or use twitter if you’d like to discuss this with me,

Thanks,

Ben

@benrogersedu

1 Comment